Max Ernst

Facilité

Artist

Max Ernst

(1891, Brühl - 1976, Paris), German

Original Title

Facilité

Date1923-1924

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions65 × 54,5 cm

Classificationspaintings

Credit LineKunsthalle Praha

Status

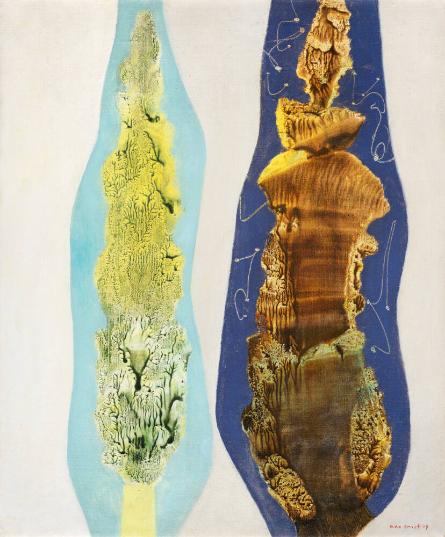

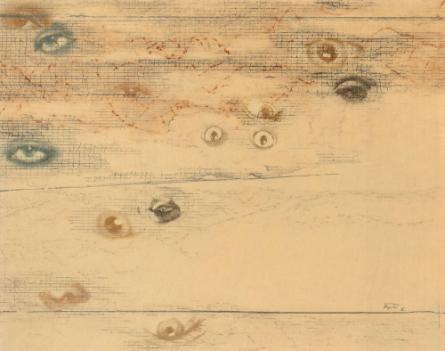

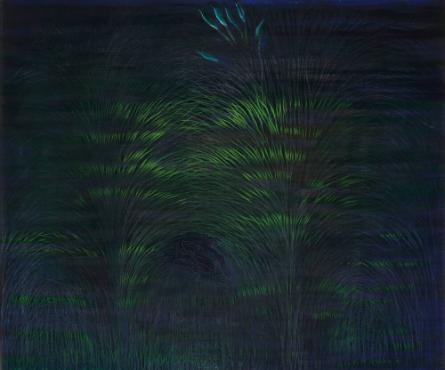

On viewDescriptionMax Ernst is generally considered one of the foremost proponents of the European avantgarde. He was a founding figure of the international Dadaist movement and the Surrealist Group of Paris. Ernst’s work tended to foreshadow the general tendencies of the wider art scene. His artistic practice closely engaged with the realm of dreams, with his works stemming from marked imaginative tendencies, irrational mysteriousness, a fusion of the real and the dreamed, and an exploration of subconscious feelings. His art also drew on his knowledge of psychology, philosophy, and literature. Ernst’s innovative artistic techniques, developed as new means of spurring the imagination, significantly influenced the surrealist movement. In 1925, he invented the technique of frottage, based on emphasizing structure and haptic materiality; later, he also worked extensively with grattage and decalcomania, using these techniques to imbue his oil paintings with a plethora of diverse structures. His approach to art is defined by a gaze rooted in collage and the contrasts of different surfaces. Ernst’s early Dadaist work is infused with dark, sarcastic humor, but differs from the anarchist current of Dadaism in its imaginative impulses and aesthetic treatment of the artwork. His work from 1923 onward is associated with surrealist painting. It remained rooted in collage, which allowed Ernst to combine disjunct elements and consequently produce new meanings and connotations. A motif frequently appearing in these works are forests, which Ernst used to portray unsettling phenomena from the natural world and to combine elements of the animate and the inanimate, the biological and the technological. Depictions of hybrid monsters and apparitions, first painted in the latter half of the 1930s, can be understood as a dark, catastrophic prediction of the looming wartime destruction. During the war, Ernst worked with sculpture and also with decalcomania, expanding the printing process from gouache to oil painting and consequently producing remarkably rich and varied structures imbued with a subtle eroticism. Ernst’s work was also shaped by his travels in the Southwest of the USA, where he encountered “primitive” American art and Native American art, which influenced his method of combining decalcomania with other techniques. At the end of World War II, his work evolved toward a simplification of pictorial forms and a use of brighter color palettes. In the mid-1960s, Ernst returned to collage, combining several different approaches within a single work. These painting-collages are often imbued with pure lyricism, subtle humor, and metaphorical imagery. The cosmos became a central motif of these works, as did the relationship between the microcosm and the macrocosm.

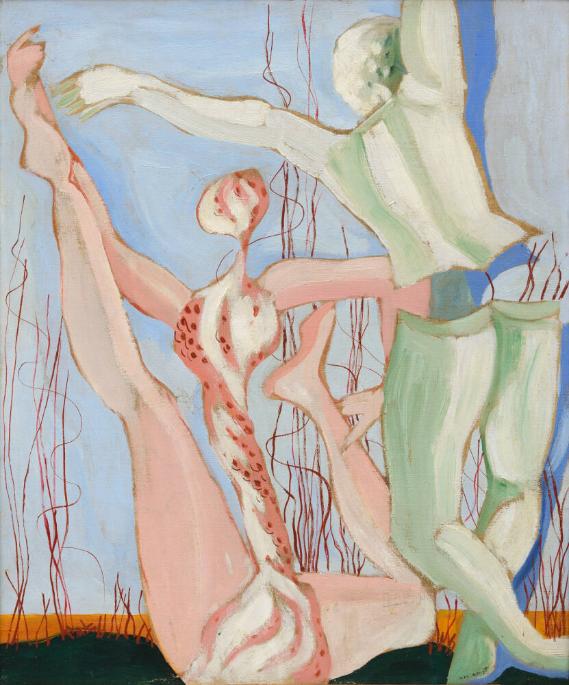

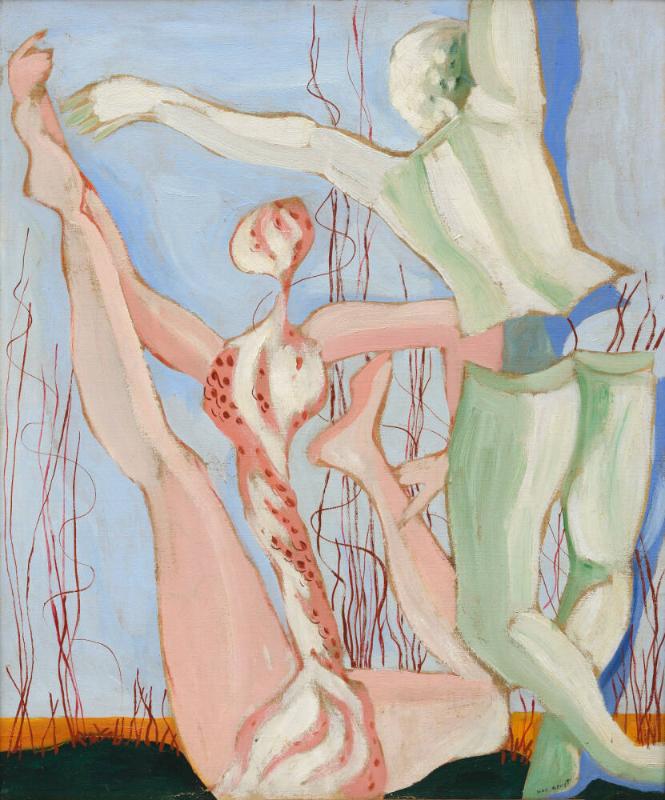

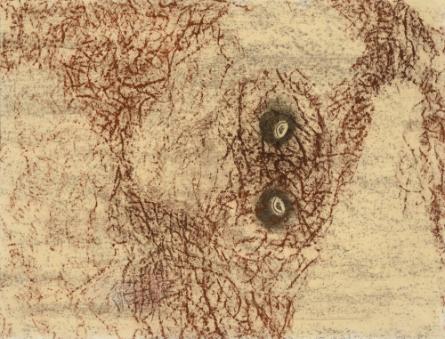

Max Ernst painted Facilité during 1923 and 1924, shortly preceding the publication of the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) by André Breton, who worked with Ernst in the circle centered around the journal Littérature at the time. Following years of Dadaist experimentation, this work saw Ernst return to oil painting and focus more closely on portraying subconscious imagery and dreams, drawing on the method of pure psychic automatism. The painting depicts two mysterious, fragmented figures—a woman and a man—performing a ritualistic dance in an environment resembling the ocean floor. The motif of the two lovers is rendered in a style blending figurative and organic-vegetative morphologies, imbuing the painting with strong poetic qualities. Therefore, the work can be seen as a type of visual poem, which was called for by Bréton in the Manifesto of Surrealism. With this painting, Ernst also anticipated the surrealist focus on eroticism and symbolic imagery, reifying the realm of subconscious ideas.

Max Ernst (1891, Brühl – 1976, Paris) was born in Germany but predominantly worked in Paris and New York City. During World War I, he was deployed on the Western front. After the war, Ernst settled in Cologne, where he took part in the activities of the international Dadaist movement. In 1921, he presented his work in Paris for the first time, exhibiting at the gallery Au Sans Pareil alongside S. T. Baargeld and Jean Arp; the exhibition was organized by André Breton. The following year, Ernst moved to Paris and developed ties with Paul Eluard and the surrealist literary circles. His first solo exhibition took place in 1931 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. In 1936, his work was included in the large-scale exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Ernst’s art also regularly featured in exhibitions presenting international surrealist artists. However, a wider recognition and appreciation of his work would only occur after World War II. In 1937, the Nazi regime classified his work as Entartete Kunst (degenerate art); at the onset of World War II, he was briefly interned as a German citizen, before fleeing from the Gestapo an emigrating to the USA in 1941. He is generally cited as an important influence for the young generation of American artists associated with abstraction and action painting, which Ernst himself saw as another method of developing the imagination. In 1948, Ernst became a US citizen, but he moved back to Europe in the early 1950s. In 1952, he was invited to give a series of lectures at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. During this stay, he became acquainted with the landscapes of the Pacific Ocean, which inspired some of his subsequent paintings. In 1954, he received the grand prize at the 27th Venice Biennale. In 1958, he was awarded French citizenship and a largescale retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. The following two decades saw retrospectives of Ernst’s work at institutions such as the Museum of Modern art in New York City, the Tate Gallery in London, the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and the Grand Palais in Paris. Today, his work is held in the collections of prominent museums around the world. Ernst’s legacy is also managed by the Max Ernst Museum, based in his hometown of Brühl. In the Czech context, Ernst’s surrealist works were featured in the large group exhibitions L’Ecole de Paris (1931) and Poesie 1932, where they represented contemporary surrealism. The Czech art scene had particular appreciation to his artistic techniques, which aligned with the demand for surrealist psychic automatism.

Max Ernst painted Facilité during 1923 and 1924, shortly preceding the publication of the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) by André Breton, who worked with Ernst in the circle centered around the journal Littérature at the time. Following years of Dadaist experimentation, this work saw Ernst return to oil painting and focus more closely on portraying subconscious imagery and dreams, drawing on the method of pure psychic automatism. The painting depicts two mysterious, fragmented figures—a woman and a man—performing a ritualistic dance in an environment resembling the ocean floor. The motif of the two lovers is rendered in a style blending figurative and organic-vegetative morphologies, imbuing the painting with strong poetic qualities. Therefore, the work can be seen as a type of visual poem, which was called for by Bréton in the Manifesto of Surrealism. With this painting, Ernst also anticipated the surrealist focus on eroticism and symbolic imagery, reifying the realm of subconscious ideas.

Max Ernst (1891, Brühl – 1976, Paris) was born in Germany but predominantly worked in Paris and New York City. During World War I, he was deployed on the Western front. After the war, Ernst settled in Cologne, where he took part in the activities of the international Dadaist movement. In 1921, he presented his work in Paris for the first time, exhibiting at the gallery Au Sans Pareil alongside S. T. Baargeld and Jean Arp; the exhibition was organized by André Breton. The following year, Ernst moved to Paris and developed ties with Paul Eluard and the surrealist literary circles. His first solo exhibition took place in 1931 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. In 1936, his work was included in the large-scale exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Ernst’s art also regularly featured in exhibitions presenting international surrealist artists. However, a wider recognition and appreciation of his work would only occur after World War II. In 1937, the Nazi regime classified his work as Entartete Kunst (degenerate art); at the onset of World War II, he was briefly interned as a German citizen, before fleeing from the Gestapo an emigrating to the USA in 1941. He is generally cited as an important influence for the young generation of American artists associated with abstraction and action painting, which Ernst himself saw as another method of developing the imagination. In 1948, Ernst became a US citizen, but he moved back to Europe in the early 1950s. In 1952, he was invited to give a series of lectures at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. During this stay, he became acquainted with the landscapes of the Pacific Ocean, which inspired some of his subsequent paintings. In 1954, he received the grand prize at the 27th Venice Biennale. In 1958, he was awarded French citizenship and a largescale retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. The following two decades saw retrospectives of Ernst’s work at institutions such as the Museum of Modern art in New York City, the Tate Gallery in London, the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and the Grand Palais in Paris. Today, his work is held in the collections of prominent museums around the world. Ernst’s legacy is also managed by the Max Ernst Museum, based in his hometown of Brühl. In the Czech context, Ernst’s surrealist works were featured in the large group exhibitions L’Ecole de Paris (1931) and Poesie 1932, where they represented contemporary surrealism. The Czech art scene had particular appreciation to his artistic techniques, which aligned with the demand for surrealist psychic automatism.