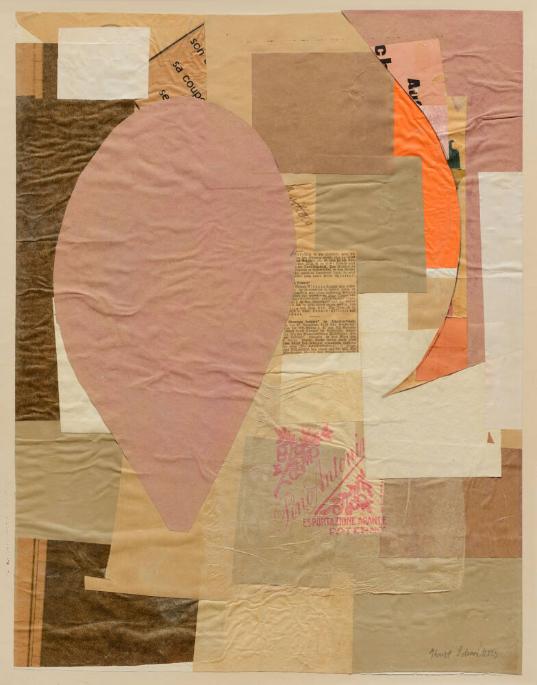

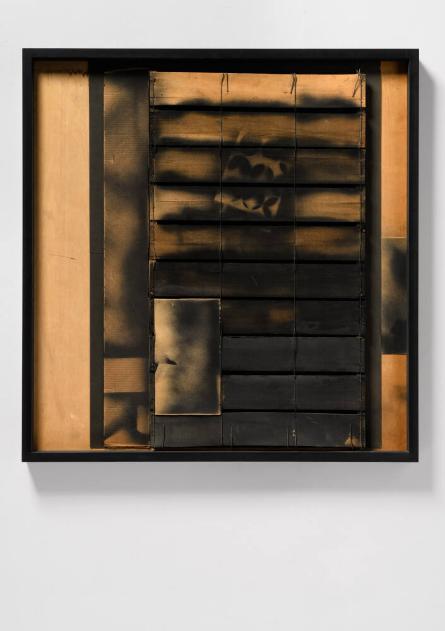

Kurt Schwitters

Untitled (Pino Antoni)

Artist

Kurt Schwitters

(1887, Hannover - 1948, Kendal), German

Original Title

Ohne Titel (Pino Antoni)

Date1933-1934

Mediummixed media on paper

Dimensions86,5 × 72,5 × 5,5 cm

Classificationscollages

Credit LineKunsthalle Praha

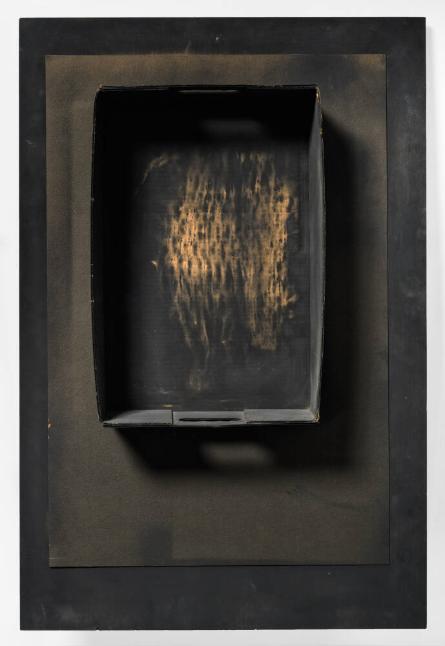

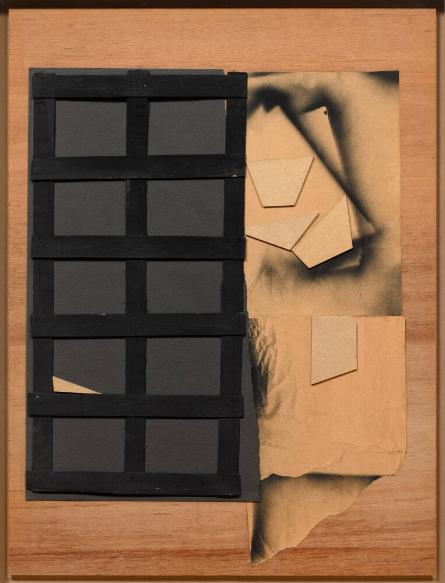

DescriptionKurt Schwitters was a prominent figure of the interwar avantgarde, whose practice was defined by extensive experimentation and a search for new forms of artistic expression. Although his art bared similarities with the work of the surrealists, De Stijl, and the Dada movement, Schwitters always maintained his own distinctive style based on a unique artistic approach. From 1919 onward, he began using the term “merz”, derived from the word Kommerz (commerce) in relation to his art, applying it to all his works. For Schwitters, merz denoted a new beginning and an expression of his visionary approach focused on creative freedom and the positive power of change, which he saw abstract art as representative of. It also signaled a fusion of art and life, thus aiming to use all possible materials for artistic purposes. His works made of found materials marked a reaction against the conservative social climate and elicited a significant degree of shock at the time. In 1919, his work departed from traditional painting toward abstract collages, which abandoned the concept of traditional vanishing point-based perspective. Schwitters’s primary aim was to demonstrate that even destruction and waste can give rise to something beautiful and harmonious. He created abstract compositions incorporating cut-out pieces of text as well as typographic and numeric symbols conveying a range of biographic and contemporary information. These clues, which include prints with fragments of news headlines, commercials, movie tickets, tram tickets, cigarette packages, and chocolate wrappers, symbolize contemporary events and lifestyles, forming an associative framework concentrating much of the zeitgeist of Germany in the 1930s as it grappled with economic crisis, rapid devaluation of its currency, and widespread strikes. A distinctive quality of these collages is their sensitively composed color palettes as well as the traces of wear and tear visible on the individual elements. While initially these collages mainly bore dark and melancholic color palettes, during the mid-1920s an affiliation with the ideas of the Dutch art group De Stijl led Schwitters to use only primary colors and relatively sizeable, unicolored planes with clear divisions. During the 1930s, observation of lighting conditions in Norway lead to a brightening of his palette, which also began to incorporate various tones of grey. His later material paintings then included a significant amount of painting while also incorporating wood, which imbued them with a more informalist dimension. Schwitters’s interest in creating a gesamtkunstwerk also led him to produce his first merz building—a fantastical structure which he built over many years, and which occupied most of his studio in Hannover. This spatial-sculptural piece can be understood as a forerunner of immersive installations. Schwitters himself described it as an artwork, an abstract sculpture which can be entered and which changes in connection with the viewer’s movement. Unfortunately, the installation was destroyed during World War II. His second merz building, created during his stay in Norway, did not survive either. Schwitters later began creating a third merz building after moving to England. During the 1940s, he also created sculptures and spatial assemblages marked by a significant painterly dimension.

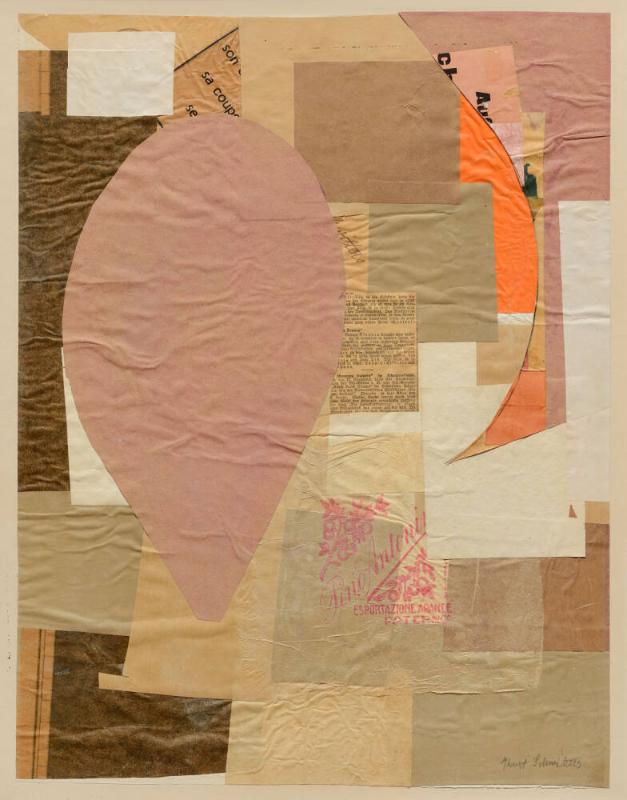

This collage was created during 1933 and 1934 and is marked by its conspicuous structuring. Its sensitive composition and muted colors evidence the substantial painterly value of the work. It comprises several layers of geometric and organic shapes, which draw inspiration from the abstract tendencies prominent on the contemporary Parisian art scene. At the time, Schwitters himself was a member of the international art group Abstraction-Création, which sought to bring together artists developing an abstract artistic language. On the other hand, however, Schwitters’s collage also contains references to external reality—a ticket from Pino Antoni (a company exporting oranges), newspaper clippings, and fragments of other printed materials, all of which contradict the contentual norms of abstract art. During this time, Schwitters regularly visited his son Ernst in Norway, and the organic, monochrome forms could have therefore been inspired by the rural environment around Lysaker, nearby Oslo, which also influence the muted color palette of the piece. These elements also demonstrate the originality of Schwitters’s artistic trajectory, which found affiliation with certain contemporary artistic tendencies but simultaneously maintained its own autonomy and connection with the surrounding world.

German artist Kurt Schwitters (1887, Hannover – 1948, Kendal) first attended the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hannover between 1908 and 1909, and subsequently the Kunstakademie Dresden from 1909 to 1914. During World War I he worked as a draftsman in the German army. In 1919, he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin, where he introduced his first merz paintings and struck up friendships with Jean Arp and Raoul Hausmann. In 1920, he exhibited at the Société Anonyme in New York City. During the early 1920s, he created poems based on words, letters, and numbers, which aimed to explore with the foundations of language and a reduction of communication devices. In 1922, Schwitters and Arp attended the Congress of Constructivists and Dadaists in Weimar. The following year, he began publishing the magazine Merz, in which he juxtaposed different artistic orientations—such as cubism, Dada, surrealism, suprematism, De Stijl, and Bauhaus—and propagated a new aesthetic of typography, painting, and sound. During the 1920s, Schwitters also often visited various European artistic hubs, such as Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, Prague, where he showcased innovative artistic forms influenced by Dadaism and anarchism via performances and public appearances. He organized his Dadaist performances in Prague and Brno together with Raoul Hausmann and Richard Huelsenbeck. The influence of Dadaism in the Czech context was most evident in the early stages of the Devětsil Artistic Federation and, particularly, in the activities of the Liberated Theatre. Schwitters also had solo exhibition in Prague between 1926 and 1927, where he presented a selection of collages spanning the last six years of his work. The collages Nr. 3 Prag and Nr. 6 Aus were created during his stay in Prague, or at least from materials which he collected while in Prague, such as tram tickets and printed materials. In 1929, Schwitters’s work featured in the exhibition Abstrakte und surrealistiche Malerei und Plastik (Abstract and Surrealist Painting and Sculpture) at the Kunsthaus Zurich. In 1932, he became a member of the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création. In 1936, he took part in exhibitions Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastical Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Having been included on the Nazi list of “degenerate” artists, he decided to emigrate in 1937. He settled in the Norwegian city of Lysaker, where he would create his second merz building and also engage landscape painting. After the German invasion of Norway in 1940, Schwitters fled to the United Kingdom, where he spent over a year in various internment camps. He subsequently settled in London, before moving to the Lake District in 1945, where he worked on his third merz building, which would, however, remain unfinished. His works are included in the collections of institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. A number of his works can also be found in his hometown of Hannover—in 2001, the Kurt and Ernst Schwitters Foundation and the Kurt Schwitters Archive were founded, both affiliated with the Sprengel Museum Hannover.

This collage was created during 1933 and 1934 and is marked by its conspicuous structuring. Its sensitive composition and muted colors evidence the substantial painterly value of the work. It comprises several layers of geometric and organic shapes, which draw inspiration from the abstract tendencies prominent on the contemporary Parisian art scene. At the time, Schwitters himself was a member of the international art group Abstraction-Création, which sought to bring together artists developing an abstract artistic language. On the other hand, however, Schwitters’s collage also contains references to external reality—a ticket from Pino Antoni (a company exporting oranges), newspaper clippings, and fragments of other printed materials, all of which contradict the contentual norms of abstract art. During this time, Schwitters regularly visited his son Ernst in Norway, and the organic, monochrome forms could have therefore been inspired by the rural environment around Lysaker, nearby Oslo, which also influence the muted color palette of the piece. These elements also demonstrate the originality of Schwitters’s artistic trajectory, which found affiliation with certain contemporary artistic tendencies but simultaneously maintained its own autonomy and connection with the surrounding world.

German artist Kurt Schwitters (1887, Hannover – 1948, Kendal) first attended the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hannover between 1908 and 1909, and subsequently the Kunstakademie Dresden from 1909 to 1914. During World War I he worked as a draftsman in the German army. In 1919, he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin, where he introduced his first merz paintings and struck up friendships with Jean Arp and Raoul Hausmann. In 1920, he exhibited at the Société Anonyme in New York City. During the early 1920s, he created poems based on words, letters, and numbers, which aimed to explore with the foundations of language and a reduction of communication devices. In 1922, Schwitters and Arp attended the Congress of Constructivists and Dadaists in Weimar. The following year, he began publishing the magazine Merz, in which he juxtaposed different artistic orientations—such as cubism, Dada, surrealism, suprematism, De Stijl, and Bauhaus—and propagated a new aesthetic of typography, painting, and sound. During the 1920s, Schwitters also often visited various European artistic hubs, such as Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, Prague, where he showcased innovative artistic forms influenced by Dadaism and anarchism via performances and public appearances. He organized his Dadaist performances in Prague and Brno together with Raoul Hausmann and Richard Huelsenbeck. The influence of Dadaism in the Czech context was most evident in the early stages of the Devětsil Artistic Federation and, particularly, in the activities of the Liberated Theatre. Schwitters also had solo exhibition in Prague between 1926 and 1927, where he presented a selection of collages spanning the last six years of his work. The collages Nr. 3 Prag and Nr. 6 Aus were created during his stay in Prague, or at least from materials which he collected while in Prague, such as tram tickets and printed materials. In 1929, Schwitters’s work featured in the exhibition Abstrakte und surrealistiche Malerei und Plastik (Abstract and Surrealist Painting and Sculpture) at the Kunsthaus Zurich. In 1932, he became a member of the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création. In 1936, he took part in exhibitions Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastical Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Having been included on the Nazi list of “degenerate” artists, he decided to emigrate in 1937. He settled in the Norwegian city of Lysaker, where he would create his second merz building and also engage landscape painting. After the German invasion of Norway in 1940, Schwitters fled to the United Kingdom, where he spent over a year in various internment camps. He subsequently settled in London, before moving to the Lake District in 1945, where he worked on his third merz building, which would, however, remain unfinished. His works are included in the collections of institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. A number of his works can also be found in his hometown of Hannover—in 2001, the Kurt and Ernst Schwitters Foundation and the Kurt Schwitters Archive were founded, both affiliated with the Sprengel Museum Hannover.